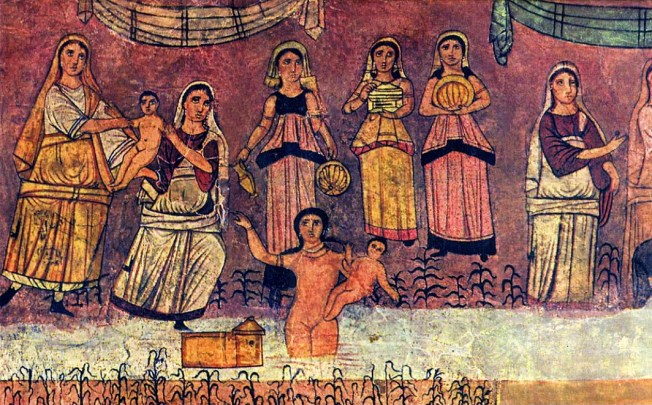

“Moses in a Basket”

Exodus 1:15-2:6 – July 7, 2019

On social media, one sure way to get loads of “likes” and “shares” is to post the photo of a cute baby. So many people love seeing photos of little babies looking adorable. And when photos of crying or unhappy babies are posted, many people pour out their sad, shocked, and comforting emotions in their responses online.

Is it much different in our Scripture reading today from Exodus? As we hear about the infants born to the Israelite women in Egypt so long ago, I suspect many in our congregation are sad and shocked, and wish to comfort those women and families involved.

And yet—this narrative about infants from Exodus has a much starker, darker impact, as we read it over again in the clear light of day. With the typical economy of words that Hebrew often employs, our narrative opens with: “8 Then a new king, to whom Joseph meant nothing, came to power in Egypt.” In other words, a number of generations had passed, and as commentator Karla Suomala suggests “the new king didn’t remember Joseph’s role in keeping the Egyptians alive during a time of famine or simply chose to ignore this piece of history. It seems to be more willful than a simple act of forgetting.” [1]

The people of Israel, resident aliens living in Egypt for several hundred years, have become extremely numerous. So numerous, in fact, that the new Pharaoh and other racist Egyptian leaders feared the people of Israel would be guilty of insurrection or an alliance with a foreign nation. The Egyptians ruthlessly worked them even harder, but they continued to multiply and grow as a sub-people group within the nation.

I give a trigger warning, since this sermon is going to speak of some horrible events.

“Further compounding [Pharaoh’s] false statement, is a clear strategy to create an “enemy within” and to stir up fear of the foreign or immigrant other. The Pharaoh then wastes no time in putting a plan together to deal with this dangerous element in their midst.” [2] Pharaoh and the other leaders became so fearful and anxious that they come up with a nefarious scheme—killing all the Jewish boy babies, from that point onward.

We take a side trip to consider women in healthcare, specifically working as midwives. This work as midwives outside the home has been an accepted thing for certain women to do for millenia. The two women we look at come at the beginning of Exodus, in the middle of this narrative about the Israelite—or, Hebrew boy children.

These women were diligent in their work. We even know the names of these midwives—Shiprah and Puah. The biblical writer honors them by recording their names for posterity. Plus, they were God-fearing women, who understood their work was important in God’s eyes.

As we know, Pharaoh’s evil plan was to command the Hebrew midwives to kill all baby boys, to commit male infanticide, yet allow the baby girls to live. This is a slow yet sure way of eradicating Egypt’s problem population. What do we think about such horrendous acts of cruelty? No, even worse, acts of murder? What would you consider doing, if you had been in the place of these Hebrew midwives?

The midwives Shiprah and Pual were civil servants; they worked for the Egyptian government, and so the all-powerful Pharaoh was their ultimate boss. However, Pharaoh and his cronies did not have much power. Pharaoh needed to meet with the Israelite midwives in a huge turnover in power. Imagine, we are faced with the question: where—with whom—does true power reside?

Apparently, Pharaoh is not aware of this power differential. What is more, Pharaoh tries to deputize these Hebrew midwives to do his dirty work for him. He does not want to get his hands (or the hands of his fellow Egyptian leaders) bloody.

The midwives are honorable and God-fearing, and most probably cannot even consider killing the newborn infants they assist bringing into the world. However, when Pharaoh asks them why they are not killing the baby boys, “the midwives respond by playing to his own stereotypes about immigrants and their breeding habits. “Because the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women; for they are vigorous and give birth before the midwife comes to them,” they say.” [3]

Here we see that racist stereotypes are sadly perpetuated from generation to generation. Has this frightening, common, xenophobic mindset changed today? I think not.

The Pharaoh clearly sees that he won’t be able to convince the Israelites to kill their own children. So, he and other racist, xenophobic Egyptian leaders turn to the Egyptian population, telling them to throw the Jewish baby boys into the Nile River. This is where we pick up with the story of Moses. His mother gave birth to Moses in secret, hid him for three months, and then finally did put him in the Nile River—in a floating, waterproof basket.

We follow Miriam, Moses’s older sister, watching from the riverbank, as Pharaoh’s daughter finds the floating basket. Pharaoh’s daughter is charmed with the darling baby who she correctly identifies as a Jewish baby, spies Miriam nearby, and asks whether Miriam can find a wet nurse for this baby she decides on the spot to adopt. Thus, the adopted Moses is suckled by his own mom—and even paid to nurse her own child. Such are the amazing incidents that happen in God’s providence.

One fascinating insight about the male Pharaoh and the female midwives: one of the most striking points of this section is the fact that the text names the midwives. Why do we need to know the names of these two women, Shiphrah and Puah, who never appear again in the story? Names are very important in the Book of Exodus. Moses’s sister Miriam is named, too, further on in the book.

Who remains nameless? Pharaoh. Pharaoh is unnamed. Pharaoh’s royal family members are unnamed. Pharaoh’s officers are unnamed. Pharaoh’s royal advisors are unnamed. Every Egyptian in the book of Exodus remains nameless. All public figures in Egypt take great efforts at self-promotion and control. [4] But when God steps in and raises up the women in this story, we need to sit up and take notice.

A final act of defiance to the Pharaoh’s authority and will comes from his own daughter. Moses will grow up under the protection of the princess even before he is officially adopted. [5] Sure, we can see the patriarchal mindset and attitude shown in the Bible remains deeply entrenched, through the centuries. However, in God’s providence and outworking in these connected situations, we can see defiance and subversion of Pharaohs’ commands, even from within his own house at the hands of his own daughter.

God be praised. Yes, there is continuing horror, despair, death and destruction. But, God’s purposes shine through all the darkness. Moses rose to prominence, to lead his people out of Egypt. And, God’s purposes continue to shine through.

That is something to truly celebrate. Alleluia, amen.

(Suggestion: visit me at my regular blog for 2019: matterofprayer: A Year of Everyday Prayers. #PursuePEACE – and my other blog, A Year of Being Kind . Thanks!

This entry was tagged angry, arrogant, coat of many colors, dysfunctional, favorite, Genesis 37, God’s purposes, hurt feelings, Joseph, praise God, reconcile, sibling rivalry.

[1] http://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=3380

Commentary, Karla Suomala, Preaching This Week, WorkingPreacher.org, 2017.

[2] Ibid.

[3] http://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=3380

Commentary, Karla Suomala, Preaching This Week, WorkingPreacher.org, 2017.

[4] https://juniaproject.com/midwives-vs-pharaoh-exodus-question-of-power/

[5] http://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=972

Commentary, Exodus 1:8-2:10, Amy Merrill Willis, Preaching This Week, WorkingPreacher.org, 2011.